In Asian myths, no creature is as impressive as the dragon. For Vietnamese peasants, the dragon was a vivid symbol of the fourfold deity-clouds, rain, thunder and lighting. Represented by an S shape, dragons are depicted on artifacts dating back to the Dong Son-Au Lac culture, which existed in northern Vietnam in the first millennium B.C. Later came the cult of Tu Phap, or the Four Miracles. Long ago stargazers identified the Dragon constellation made up of seven stars arranged like an S. The brightest star is the Mind (Tam), also known as the Divine (Than) star. The word Than may also be read as Thin (Dragon), which denotes the third month of the lunar calendar and represents the Yang vital energy.

In Asian myths, no creature is as impressive as the dragon. For Vietnamese peasants, the dragon was a vivid symbol of the fourfold deity-clouds, rain, thunder and lighting. Represented by an S shape, dragons are depicted on artifacts dating back to the Dong Son-Au Lac culture, which existed in northern Vietnam in the first millennium B.C. Later came the cult of Tu Phap, or the Four Miracles. Long ago stargazers identified the Dragon constellation made up of seven stars arranged like an S. The brightest star is the Mind (Tam), also known as the Divine (Than) star. The word Than may also be read as Thin (Dragon), which denotes the third month of the lunar calendar and represents the Yang vital energy.

Dragons were also associated with kingship. Every Vietnamese person knows the legend of Lac Long Quan and Au Co. Lac Long Quan (King Dragon of the Lac Bird Clan) is known as the forefather of the Vietnamese people. He is said to have been the son of a dragon, while his wife, Au Co, was the child of a fairy. Their eldest son, King Hung, taught the people to tattoo their chests, bellies and thighs with dragon images to protect themselves from aquatic monsters.

During the Ly Dynasty (11th to early 13th centuries), the dragon became a common decorative motif in plastic arts. In the royal edict on the transfer of the capital to Thang Long in 1010, it was written: “The Capital is chosen due to the lay of the land, which affects a coiling dragon and a sitting tiger”.

During the Ly Dynasty (11th to early 13th centuries), the dragon became a common decorative motif in plastic arts. In the royal edict on the transfer of the capital to Thang Long in 1010, it was written: “The Capital is chosen due to the lay of the land, which affects a coiling dragon and a sitting tiger”.

Legend has it that on the sunny day when the royal barge landed at Dai La, the king saw a golden dragon rise into the sky. Taking this as a good omen, he named the new capital Thang Long, or City of the Soaring Dragon. The modern city of Hanoi stands on this same site.

The Ly king had a cluster of shops and inns built up to the walls of an ancient temple once dedicated to the dragon deity. One night, the dragon deity revealed himself in the form of a violent northerly wind, which knocked down all of the houses but left the temple intact. Following this event, the king cheerfully proclaimed: “This is the Dragon God, who takes his charge over earthly affairs”.

The Ly king had a cluster of shops and inns built up to the walls of an ancient temple once dedicated to the dragon deity. One night, the dragon deity revealed himself in the form of a violent northerly wind, which knocked down all of the houses but left the temple intact. Following this event, the king cheerfully proclaimed: “This is the Dragon God, who takes his charge over earthly affairs”.

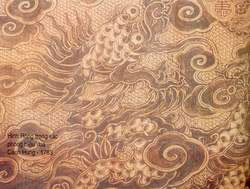

The Ly dragon was derived from India’s mythical Naga, which Southeast Asian peoples influenced by Indian mythology had transformed into a sea god. The Ly depiction of the dragon is both sophisticated and unique. The dragon’s elaborate head is raised, flame-co loured crest thrust out, a jewel held in its jaws. Its mane, ears and beard flutter gracefully behind, while its lithe, undulating body soars above the waves. The dragon was usually depicted inside a stone, a piece of wood, a bodhi leaf, or a lotus petal. Dragon images appear on the pedestals of statues of Amitabha Avalokitecvara (Kwan Kin), on cylindrical stone pillars in the hall dedicated to heaven in Thang Long Citadel, and on a five meter-high hexagonal stone pillar in Giam Pagoda in Bac Ninh province. The latter is considered by art historians to be a colossal linga. Lingas symbolize the male Yang element, while dragons symbolize the Yin element.

The Ly dragon was derived from India’s mythical Naga, which Southeast Asian peoples influenced by Indian mythology had transformed into a sea god. The Ly depiction of the dragon is both sophisticated and unique. The dragon’s elaborate head is raised, flame-co loured crest thrust out, a jewel held in its jaws. Its mane, ears and beard flutter gracefully behind, while its lithe, undulating body soars above the waves. The dragon was usually depicted inside a stone, a piece of wood, a bodhi leaf, or a lotus petal. Dragon images appear on the pedestals of statues of Amitabha Avalokitecvara (Kwan Kin), on cylindrical stone pillars in the hall dedicated to heaven in Thang Long Citadel, and on a five meter-high hexagonal stone pillar in Giam Pagoda in Bac Ninh province. The latter is considered by art historians to be a colossal linga. Lingas symbolize the male Yang element, while dragons symbolize the Yin element.

That dragons, or long, associated with royalty, are revealed by the names given to the king’s personal effects and person, such as long con (royal tunics), long chau (royal boat), long thi (royal person), and long dien (royal countenance).

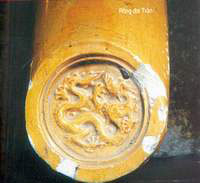

During the Tran Dynasty (early 13th to end of 14th centuries), the dragon retained the sophisticated style of the Ly dragon, yet changed to reflect the greater authority of the dynasty which defeated invading Mongol forces three times. The image became more detailed, with a large head, forked horn, four fierce a claws (stone carving in Boi Khe Pagoda), and a massive, rounded body, covered in carp scales (Pho Minh Pagoda).

The dragon took on a whole new appearance under the Le Dynasty (early 15th to end of 18th centuries). With a raised head, forked horn, wide forehead, prominent nose, large, forceful eyes, five claws, and two splayed feet, a dragon crept up the balustrade of Kinh Thien Hall’s central staircase. This fierce and imposing dragon was clearly a symbol of royal authority. Examples of Le era dragons may be found carved in stone in Co Loa Temple, carved on wooden doors in Keo Pagoda, and carved in the royal stone bed in Dinh Temple.

The Nguyen Dynasty (early 19th to mid 20th centuries) had dragons much like those of the Le. The top ridges of palace roofs were decorated with undulating dragons covered in sparkling porcelain tiles.

Initially, dragons in Vietnam were associated with water and Yin energy. Dragons were popular among the common people, who believed that rain was created by nine dragons, which took water from the sea to pour down on the rice paddies. The dragon dance, a great favorite among people from all walks of life, was used to invoke rain.

Initially, dragons in Vietnam were associated with water and Yin energy. Dragons were popular among the common people, who believed that rain was created by nine dragons, which took water from the sea to pour down on the rice paddies. The dragon dance, a great favorite among people from all walks of life, was used to invoke rain.

Many place names in Vietnam bear the word long (dragon), as in Ha Long Bay (Where the Dragon Descended) or the Cuu Long River (Nine Dragons).

Dragons occupied the top position in traditional geomancy, especially for sovereigns. It was said that Le Hoan was able to found the Anterior Le Dynasty (980-1009 A.D.) because his grandfather’s tomb was situated on a “vein in the dragon’s jaw”. The Royal Chronicle of the Restored Le Dynasty contains a story about Prince Lang Lieu, who saw a black dragon perched on his father’s tomb. “Golden dragons for emperors, black dragons for kings,” states this ancient text.

Like Chinese monarchs, Vietnamese sovereigns chose the dragon as the symbol of their power. But unlike the Chinese dragons, which were shown descending from heaven and spitting fire, the Vietnamese dragons were shown ascending from water. Though imposing and fierce, the Vietnamese dragons were never threatening.

Vietnamese Culture and Tradition

Vietnamese Culture and Tradition